There is an accompanying podcast to this blog! Listen at the bottom of the piece or follow this link.

I’ve done a few sportives over the years, but the one I’d always wanted to have a go at was L’Étape du Tour, the sportive from ASO, the organisers of the Tour de France who each year, let amateur riders attempt the equivalent of a full mountain stage of the the Tour.

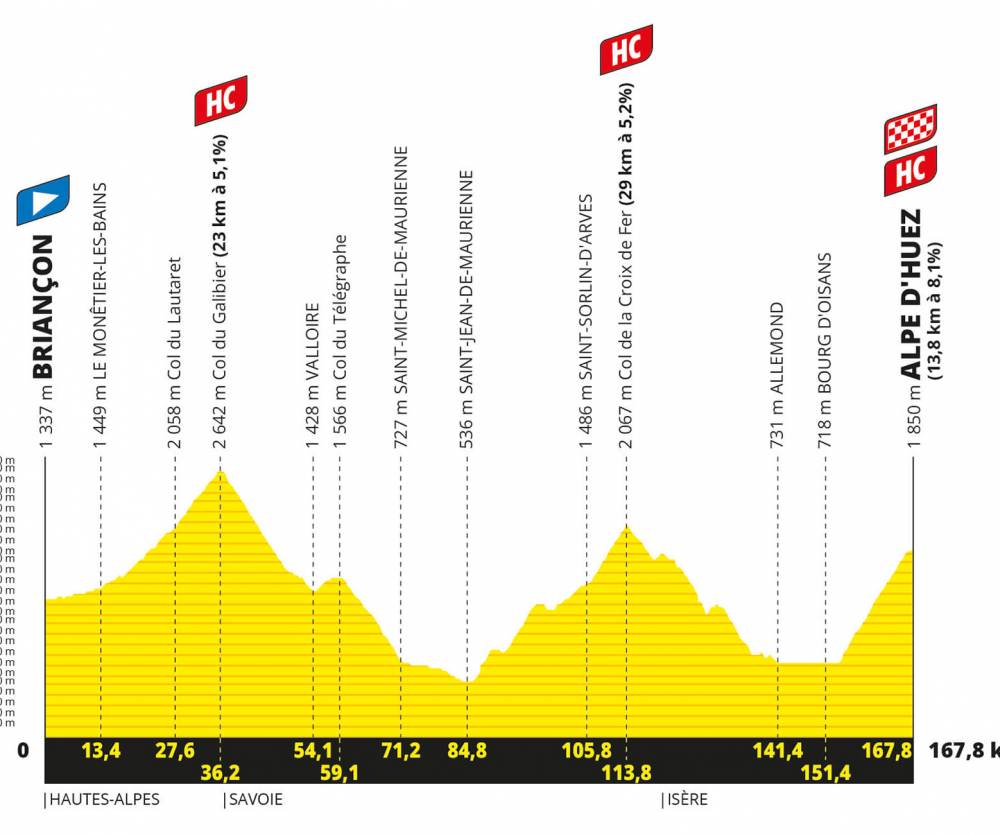

Back in October last year, when the route of the 2022 Tour de France was announced, ASO also announced the route for this year’s Étape. It would mirror stage 12 of the Tour, starting in Briançon and crossing the Col du Galibier and Col de la Croix de Fer before finishing on Alpe D’Huez. The route would be 167km, and take in 4,700m of climbing, including reaching a dizzying altitude of 2,642m on the Galibier.

I thought long and hard before I pressed the button on Sports Tours International’s website and booked my place. Could I climb that much in a single day? The distance of just over 100 miles I was confident about, but I wasn’t sure that I’d ridden much more than 5km uphill at any point in my life. South-east England is known for its hills.

Having booked my place, I started training, and over the months, I did as many hills as I could, riding routes that accumulated over 2,000m of climbing, but usually in short bursts. In June I rode a route around the Surrey and Kent hills that totalled just short of 3,000m of climbing over 190km. That I was comfortable doing that helped me believe I could do the Étape.

Meanwhile there were the virtual climbs. I use Zwift and a turbo trainer, and Zwift has it’s own Alpe du Zwift, a virtual version of the real Alpe D’Huez. By early July I had managed to climb that mountain in under 50 minutes, although having climbed two previous mountains beforehand. But from that, I knew that keeping my fluids, and particularly my salts high, would be important on the day.

Two colleagues at work were also planning to ride the Étape, one of them having done it before. So instead of risking a flight down to Geneva as I’d originally envisaged, I avoided possible delayed baggage (lots of cycles all flying the same weekend is asking for trouble), and cancelled flights because of staff shortages. Instead, the three of us would load up our bikes in my colleague’s car and we’d share the drive down through to the Alps.

The plan was a good one, because rather than arriving in Briançon directly, we instead stopped for a few days in Annecy on the way down and found our legs. We did a 100km ride up the Col du Marais (about 11km) and the 10km Leschaux. These were my first alpine climbs and indeed the longest climbs I’d ever done “IRL”.

I was pleased with my performance, and did a slightly more challenging ride that I’d found in a cycling magazine the following day. That took in the 11.5km Col de l’Arpettez with a steep average gradient of 8.5%, followed by a route that would take in the Col de Aravis which was another 11km or so at 4.5%. The former climb was on a treacherous path that hasn’t been used on a major tour, but does have a nice refuge at the top with a café for a drink and a snack. I chatted with a French cyclist who said he did the ride every year and said I’d climbed it the right way around as the decent was much better on the other side. It truly was.

I struggled on the Aravis, and was passed by a Jumbo Visma U23 rider who was climbing quickly. But I did smile for the photographer who’d set up at the top. I got myself a very good lunch in a restaurant up there before descending back down into Annecy.

The following day we headed south to Briançon where I met up with the team from Sports Tours International. They had some very helpful bike mechanics on hand who helped finetune my disc breaks.

I also visited the Étape’s expo where riders had to sign in and could tour stands that displayed some of the latest and greatest bikes as well as every kind of sports nutrition that you could want. I stuck with my tried and tested Science in Sport products (they sponsor The Cycling Podcast), and in any case, the idea of trying a new product ahead of a big event like the Étape didn’t strike me as sensible.

At the expo, there’s a banner proudly displaying the names of all the riders taking part – and of course everyone gets photos.

On the Saturday before the event, I didn’t have a lot to do. I may have made a return visit to the expo to buy a keenly priced pair of sunglasses, but while some of the nearby mountains like the Col de Izoard were screaming out to be ridden, I knew that I needed to rest up ahead of the race. So I got a cable car to the top of one the mountains overlooking the city and found a walking route down. In the afternoon, I took my bike for a quick spin up to the old town which is steep, but was just enough to keep my legs turning.

I settled in for an early night because I needed to have my bags packed early so they could be transported to my next hotel ahead of the race which started at 7am the following morning.

After a full breakfast, I cycled down nervously with others to the startline.

When you register for the Étape, you have to provide lots of stats about your fitness and estimate what time you thought you’d complete the route in. I simply had no idea and went back and forth with myself trying to work it out. In distance terms, six hours or so would be fair, but that didn’t really take into account the altitude.

In the end, the Étape organisers placed me in pen 11, towards the back of the 14 pens in total. Events like this commonly put faster participants at the front and slower ones at the rear, which is fine and makes sense. But it the Étape has strict cut-offs at various points across the course because it’s run on closed roads. That inconveniences the locals a lot, so they publish a set of times when riders must have reached each point along the route. Failure to do so means that a fleet of coaches operating at “broom wagons” would pick you up and ferry you to the finish.

The issue with all of this is that the first riders set off at 7am, while the last don’t leave until 9am giving the weaker riders much less time to beat the cut-offs. That all made me a little nervous, but I tried not to think too much about it.

In my start pen I chatted to a couple of fellow Brits who I could identify from the flags on the race bibs. Each rider was given a chipped race number to attach to their bike and another to pin to the back of their jersey. These also displayed their first name and the flag of their country. However, I must have missed a dropdown online because mine had defaulted to a French flag. In due course this would mean a lot of other riders engaging with me in French along the route! Let’s just say I tended to nod, smile and say “Oui!” a lot.

A chatted to a rider from Diss and another from near Manchester, and we discussed the impact of Brexit with a French rider from Toulouse who spoke good English. We were awaiting our departure.

At 8:22am on the dot, our pen was released and as we crossed the start line, “Didi the Devil” (a German who appears roadside at the Tour de France most years) sent us on our way.

The route out of Briançon was uphill from the start as we headed towards the Col du Lauterat en route to the Galibier. It’s hard to know how to pace yourself when you have such a big day ahead of you, but I knew that I shouldn’t be burning any matches on the first long climb.

It would take me 90 minutes to get up to the top of the Galibier. It was still relatively early, which meant it was quite cool, but it was a clear day, and the route was stunningly beautiful. As you climbed, you could look back at the zig-zags and see thousands of riders behind you.

The landscape is open, and it was only towards the top by a large building that a big group of fans had gathered playing loud music and cheering everyone on. I could already see that some were suffering as I spun a low gear and climbed ever higher, going well beyond 2,000m in altitude.

I was lucky to be riding a relatively new bike – my Canyon Endurace SL 8 was my first ever carbon bike and also came with a full new Shimano Ultegra Di2 groupset. That meant 12 speeds on the cassette and a generous 11-34T cassette. I have been loving the smooth shifting that Di2 provides, and that massive rear 34 tooth cassette was perfect for this event. Even better was the fantastic breaking performance of the disc brakes.

At the top of the Galibier I stopped briefly to put on a wind jacket before plummeting back down the mountain.

At this point I realised that some people are demon descenders, and some people think they’re demon descenders. I’m neither even if I’m no slouch. But I didn’t want to have an accident and while I might trust in my own abilities, I don’t have that trust in others.

So I wasn’t the fasted down the mountain.

The road then briefly rose again to reach the Col du Telegraph, but coming down this side of the mountain that wasn’t a real climb.

At the bottom, after a stop for drinks and food, I headed out into quite a head wind as we followed the road up the valley towards Saint Jean de Maurienne which is where the foot of the 29km climb to the Croix de Fer began. For this part of the ride, a group of us formed a chain gang, taking turns at the front to battle the headwind. I felt like I was really racing. I was also aware I didn’t do enough pulls at the front myself. I’d make up for that.

This was simply the hardest climb of the day. By now it was now around midday as I began the climb and the temperature was rising. I could feel the heat burning as we climbed a relatively exposed climb, because even though there were sometimes trees around us, the sun was so high that they didn’t cast much in the way of shadows.

As we headed higher, I saw more riders stopping at the side of the road, resting in sheltered areas and catching their breath. I didn’t think this was a good idea, and kept churning away.

At the best of times, I’m bad at drinking enough liquids on a cycle ride. But I’d made certain that I hydrated properly this time around. I usually keep one bottle of a sports drink alongside one bottle of water so that I can rotate them. I was also trying to take on gels on a regular basis. Solid foods I mostly did at stops. I’d filled my two bottles at the bottom of the Croix de Fer, but I knew that the official drinks station 5km from the top couldn’t come soon enough.

On the roadside, unofficial stops were provided by locals who had hoses and buckets to help hydrate those in need.

When I eventually reached the stop I probably drunk two full bidons before refilling them again and heading out for the final climb to the summit.

We descended down from the Croix de Fer and it was magnificent. I suppose I should have stopped to take more photos, but I wanted to keep moving and my phone probably wouldn’t have done it justice. The Lac de Grand Maison was spectacular – but I have no photos.

Then it was along another valley road to the bottom of Alpe D’Huez. After I stopped for more drinks, I got into another chain gang. Except this time, everyone was happy to let me do all the pulling. But I just loved it. It wasn’t hard and the road was pan flat. So I just got into the drops and did 6 or 7km with everyone strung along behind me. Then the road rose a bit and everyone dropped off the back.

The ride up Alpe D’Huez was beginning.

The one thing I knew about the “Alpe” was that it was tough at the start. Actually, it was tough all the way up.

Already on Croix de Fer, I’d seen riders walking up the 10% slopes, and now there were more doing the same. When I later looked at the temperatures that my Garmin had recorded I saw that it had maxed out at 38C near the foot of the Alpe – where there was simply no wind.

Riders – including me – weaved across the road, not because of the gradient, but because they were seeking any shade they could fine.

Luckily many fans were out on Alpe D’Huez, getting their spots early for the Tour riders coming through four days later. And they were wonderful. The Dutch fans hosed us down with water, the Danish fans played terrible music really loudly that just raised smiles and had me dancing in my pedals to the beat of the music.

Somewhere around two thirds of the way up some lads were happily tipping bottles of cold water over anyone who wanted them to. I absolutely did. It was wonderful.

Although there were no official drinks stops on the climb, there’s fresh clean water in troughs all the way up the ride, and many were availing themselves of it.

But I didn’t want to stop, so kept churning way, unclear why the average gradient was “only” 8.1% while my bike computer was constantly telling me I was in double digit percentages (it’s a bit flat on the top and that brings the gradient down).

There are 21 switchbacks on the Alpe, and you count them down as they’re signposted, only to discover towards the end that they’ve cheated and that there’s a switchback “0” as well. At one point I could look up and see that there were only three switchbacks remaining – it was just that the altitude to be gained was still enormous.

Finally, having kept moving, even when an Australian woman in front of me dropped a bottle and understandably grabbed on the brakes so she didn’t lose it, nearly sending me crashing, I reached the flat(ter) section at the top. As you enter the town of the ski resort that is Alpe D’Huez, you don’t notice the gradient as much and by the final two kilometres you can put your front derailleur back into the big ring and really put your foot down.

By the end I was flying even as some crept by.

As I rounded the corner, there were hordes of people on the barriers, banging them as though at the end of a real stage of the Tour. Of course I did a sprint finish – although I’d note that the road rises a little more than you realise in the last 50m, and secondly you have to screech to a halt at the line because there’s no real over-run. The medals are handed out almost immediately.

I crossed the line and had finished.

It was wonderful.

In the end I came 3,882th out of 8,684 finishers (somewhere between 11,000 and 14,000 probably started). The top half of the event? I’ll take that!

My chip time from start to finish was 9 hours 27 minutes and 42 seconds, although my “moving” time was 8 hours 57 minutes and 4 seconds. So I stopped for almost exactly 30 minutes in total.

I was incredibly pleased to have finished and generally astonished at my ability to ride in the heat. I think that had I not gone out early to Annecy with my work colleagues, then I wouldn’t have properly acclimatised for the event.

After the race, I got some drinks with the guys at Sports Tours International, before heading back to my hotel, showering, changing, buying some beers and meeting some other finishers before going to the organisers’ “Pasta Party” where we attempted to regain some of the calories we’d burnt.

Speaking of which, my Garmin estimated that I’d 6,182 calories across the event and sweated nearly 7 litres! Some Kronenbourgs at the finish helped right that balence.

Would I do the event again?

Absolutely! Ideally in slightly cooler temperatures, and maybe not quite as demanding a stage, although I managed it and know what kind of training I’d need to do to finish.

I would hope that next time I’d get in an earlier pen. I noticed a lot of people with low numbers a long way back suggesting that many over-estimate their prowess. I also know that you need to be in peak fitness to do this. This is a big step up from many other sportives, and a few long weekend rides isn’t enough.

But yes – I’m sure I’ll be back!

Huw Owen, a fellow Cycling Podcast producer also completed this year’s Étape, and like me, it was his first time. Together we’ve made an episode of KM0 for The Cycling Podcast, and if you want to hear more of us on the road talking about our experiences, then please do listen!

Comments

2 responses to “L’Étape du Tour 2022”

Chapeau! That was a fantastic effort. I was over an hour behind you, having suffered cramps toward the top of the Croix de Fer, which I then had to manage up the final L’Alpe by stopping for a stretch every few corners. Maybe not enough salt or not acclimatised to the heat. Excuses, LOL! I also ride a Canyon Endurace SL8. Great bike and perfect for this kind of epic ride. Looking forward to next year and hoping it’s not quite so hot.

Chapeau to you too Pete!

Bad luck on the cramps. That was something I knew I was prone to on long Zwift climbs, so getting salts via sports nutrition drinks was key to me avoiding them on the day.

Definitely hoping for a slightly less extreme ride next year!